The following extract is from the research paper Education, Knowledge, and Learning. An overview of theories and research about constructionism and making by Lorraine Charles, William Rankin, and Catherine Speight. You can download it for free here.

‘Constructivism’ and ‘constructionism’ (including the subfields of ‘social constructivism’

and ‘social constructionism’) are two distinct learning methodologies. Although some teachers and theorists use these terms interchangeably, making a distinction between them and understanding their differences may prove helpful as we consider the design of learning approaches (Young and Collin 2004; Hyde 2015).

Constructivism is a theory of knowledge originated by the Swiss developmental psychologist Jean Piaget (1896–1980). Piaget argued that experience doesn’t happen in a vacuum; learners interpret their experiences based on their own prior knowledge as well as on the reported experiences of others. In other words, Piaget believed that children construct their knowledge based on what they know, who they are with, and who they are.

Because of this interplay between experience, reflection and identity as the basis for building knowledge, constructivism argues that learning happens best when it is self-directed. Self-direction occurs when learners feel they can exercise authentic control over the content and purpose of their learning; they make judgements regarding the significance and meaning of learning experiences in a way best suited to them.

However, this typically does not happen in isolated study; it is a function of the evaluation of shared and mutually interpreted experiences. Piaget’s constructivism provides a framework for understanding children’s patterns of thinking and development at different stages of learning (Ackermann 2010).

In constructionism, created by Seymour Papert (1928–2016) of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, learning happens when children are engaged in constructing meaningful artefacts or objects. Like constructivism, constructionism shares a view of learning that is about the building of knowledge structures through the internalisation of action over time.

However, in constructionism, attention is given to the manner of learning – also referred to as the ‘art of learning’ – and to understanding the relationship between the learner and the made object. Papert’s constructionism builds on Piaget’s constructivist theory. He proposed that learners construct mental models to understand the world around them, but must then manifest them in the construction of ‘objects-to-think-with’ to complete the process.

Constructionism shares constructivism’s view that learning involves ‘building knowledge structures’ through progressive internalisation of actions, but it adds the idea that this happens in contexts where learners are consciously engaged in constructing a ‘public entity’. Papert explains how his constructionist theory builds on constructivism thus:

From constructivist theories of psychology we take a view of learning as a reconstruction rather than as a transmission of knowledge. Then we extend the idea of manipulative materials to the idea that learning is most effective when part of an activity the learner experiences [involves] constructing a meaningful product.

According to constructivist theory, individual learners construct new knowledge based upon existing and innate knowledge. In other words, learners do not receive knowledge passively, but interpret what they receive, modifying it to construct new knowledge. Constructionist theorists and practitioners agree that learning is an active process, but they argue that it happens most productively when learners make (not receive) ideas and knowledge through the creation of personally meaningful projects.

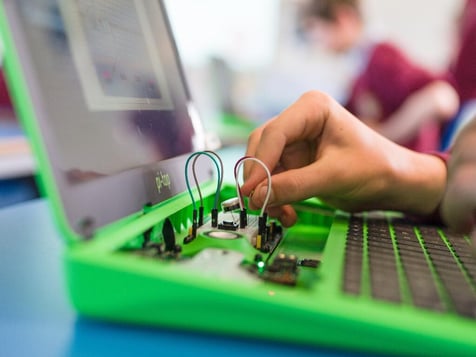

Constructionism goes beyond a superficial or simplistic idea of learning-by-doing, emphasising the roles of both design and digital technology in facilitating knowledge construction through the creation of actual artefacts.

For Papert and his fellow constructionists, the creation of new knowledge is best served in contexts where learners are consciously involved in the design and production of sharable external artefacts (such as physical projects or products), offering learners opportunities to apply the knowledge they are developing. Kafai (2006) describes the artefacts that learners create as ‘objects-to-think-with,’ where the designed artefacts, in Papert’s terms, “can become objects in the mind that help to construct, examine, and revise connections between old and new knowledge.” For truly effective learning, constructionists believe learners must make discernible objects in real-world contexts for real audiences, drawing their conclusions through creative experimentation and the feedback that results from sharing what they produce.

This emphasis on learner agency contrasts with the more academically prevalent practice of ‘instructionism,’ where knowledge is seen as a static, non-volatile object to be transmitted and absorbed. In part, this shift in emphasis from information to construction is due to more than thirty years of research, demonstrating that learners retain only minimal information from exclusively instructionist methods and they frequently have trouble transferring the information they do retain to new experiences. This difficulty in retaining and using information highlights one reason many have begun looking to constructionist educational approaches.

Constructionism does not merely impact learners, however. To provide greater opportunities for individual agency, constructionism, like socio-constructivism, proposes that teachers act as facilitators, coaching learners rather than subjecting them to lectures or step-by-step guidance (Rogoff 1994). Instructionist ‘lecturing at’ is replaced in constructionism by teachers who serve and support learners working to understand problems and develop their own solutions.

Projects, where individuals make connections between different ideas and areas of knowledge, provide an ideal environment for such learner-directed learning. This has led to momentum behind several ‘new’ learning movements, such as project- and problem-based learning and ‘maker’ education (all three of which are discussed in detail in the next chapter).

Known as ‘active learning’ for their emphasis on learner creation, these constructionist methodologies oppose the passive reception and repetition of information. Yet they also involve more than just active knowledge construction. Learners working through many constructionist approaches are also expected to reflect about their engagement in learning activities and tasks. Emphasising such metacognitive and higher-order thinking, many forms of constructionism incorporate group work, seeing collaboration as a means of driving skills and knowledge development while also offering opportunities to engender further reflection and observational opportunities that can drive metacognition.

Bonwell and Eison (1991) conclude that active forms of constructionist learning lead to better student attitudes and improvements in students’ thinking and writing. A meta-analysis study by Freeman et al., (2014) on the impact of active learning in undergraduate STEM classes shows that average examination scores improved by 6% in active learning sessions. Students in classes with traditional lecturing were 1.5 times more likely to fail than students in classes with active learning. Lecturing and the passive reception it requires of students increased overall failure rates by 55%. Active learning strategies benefitted all class sizes, although classes with fewer than 50 students saw the greatest impact.

Currently, educators are using three main forms of constructionist learning; problem based learning, project-based learning, and ‘maker’ learning. As the next chapter of this paper will outline, each approach differs from the others and offers specific advantages – and reasons for deployment. In a nutshell, in problem-based learning, teachers present a case or problem that learners must think through.

Project-based learning takes this approach to the next level by asking students to enact the solution they have developed, producing an artefact or application that reflects their attempt to respond to the case or solve the problem. ‘Maker’ learning augments project-based learning by focusing on the collaborative community and productive learning and making spaces in which learners design, develop, and build their projects.

Boiled down, constructionist learning is characterised by five key emphases

(Re)construction of knowledge: learners construct new understandings based on existing knowledge and actively make projects to test and refine the knowledge (and knowledge models) they’re developing.

Learner agency and self-directed exploration: learners take a central role in the learning process, discovering new knowledge themselves, with teachers acting as facilitators and guides rather than custodians of content.

Learning through designing and social making: learners are involved in designing and creating artefacts based on their own perspectives and ideas, getting feedback on their understanding not from external assessments (like exams) but from sharing their projects and artefacts with others.

Reflection and metacognition: learners use the projects and artefacts they make to reflect on their learning, gaining opportunities to consider their own particular learning approaches and processes as a means of facilitating understanding.

Technological literacy: learners use technology to achieve specific learning goals rather than experiencing technology as a bolt-on or after-thought.

Article adapted from the research paper Education, Knowledge, and Learning. An overview of theories and research about constructionism and making by Lorraine Charles, William Rankin, and Catherine Speight. Version 1.1, November 2018. Download it for free here.

References can be found in the original text.